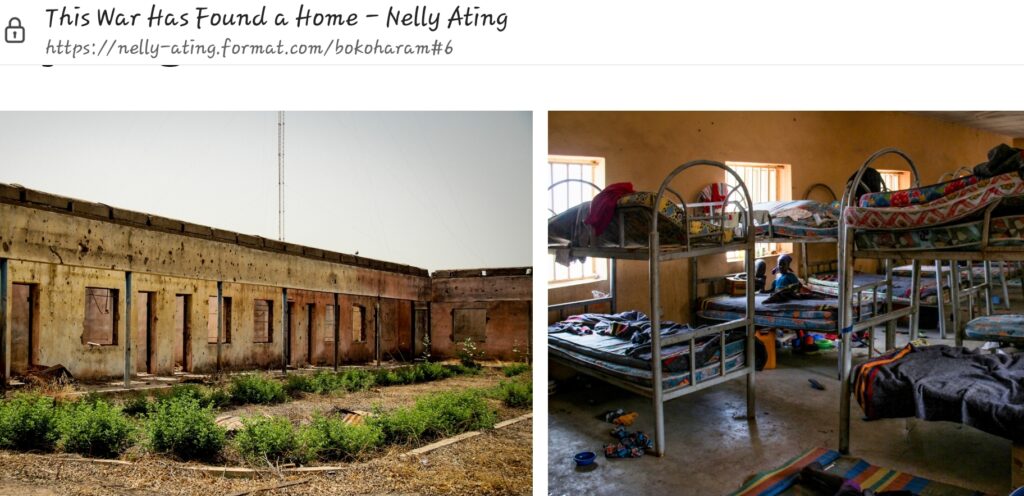

My Media Story: As an Introvert, Photography in Activism Allows my Curiosity and Creativity Intersect – Nelly Ating

Women in Photography are rare. And even more rare are women who combine photojournalism with activism. For Nelly Ating, there was no way she was going to pass up on this fantastic form of creative expression.

An as art form, photography requires a keen eye, a deeply creative soul and a touch of artistic craft in its manifestation. Photo journalism is about storytelling. Every pixel, resolution, angle of short, ISO, etc., matters. The devil, as they say, is in the details. Your attention to its art form captures the maxim: A Picture Tells a Thousand Words.

When you sit with Nelly Ating, who is a PhD student and Teaching Assistant at Cardiff University, you come away feeling like you’ve uncovered a goldmine of ideas and approach to life. In this exclusive interview with us at LightRay Media for this Special Edition on Nigeria Women in Media #NWiM Project, she allows us experience photography as she likes to depict it.

When people talk about women in media, often, what easily comes to mind is presentation on radio, newscasting on TV, or a beat reporter with a print medium or the accidental media practitioner. In your case, why photo journalism?

It was always a path I knew I would pursue. So, I studied print journalism at the American University of Nigeria (AUN). I grew up reading and developed an interest in storytelling. It was, therefore, only natural to pursue an interest that allowed my curiosity and creativity to intersect.

Nelly Ating, PhD student and Teaching Assistant at Cardiff University, UK: For the longest, my motto was: DO IT AFRAID! Whatever has been set as a limitation, despite having fears, I will still do it anyways. I told myself.

PC, Nelly Ating: https://nelly-ating.format.com/

How do you see what you do? A career or a job?

My career is always just a job. I have the mindset that we only harness half of our potentials and there are other exciting opportunities we are yet to tap. Hence, why I do not center my life around a career or a job. For now, I am even away from the field pursuing a PhD, which looks at the use of photography in activism.

Any struggles or barriers in the early days of your career you had to deal with? And had to overcome?

It was a lack of knowing myself well enough. Like every career, one needs confidence. I knew these things but failed to articulate or contextualise my experience. I am also glad I had this difficulty because it has informed me how I design photography curriculum when I train people.

Also, to overcome other challenges on the job, I am learning the ropes of understanding photographs theoretically.

That said, I don’t have any barrier, or I won’t consider them as barriers. They are like anxieties about different things. They serve as motivation into doing just anything. For the longest time, my motto was to do it, afraid. Whatever has been set as a limitation, despite having fears, I will still do it anyway.

Any stories or projects you’ve done that were the most impactful in the course of your career?

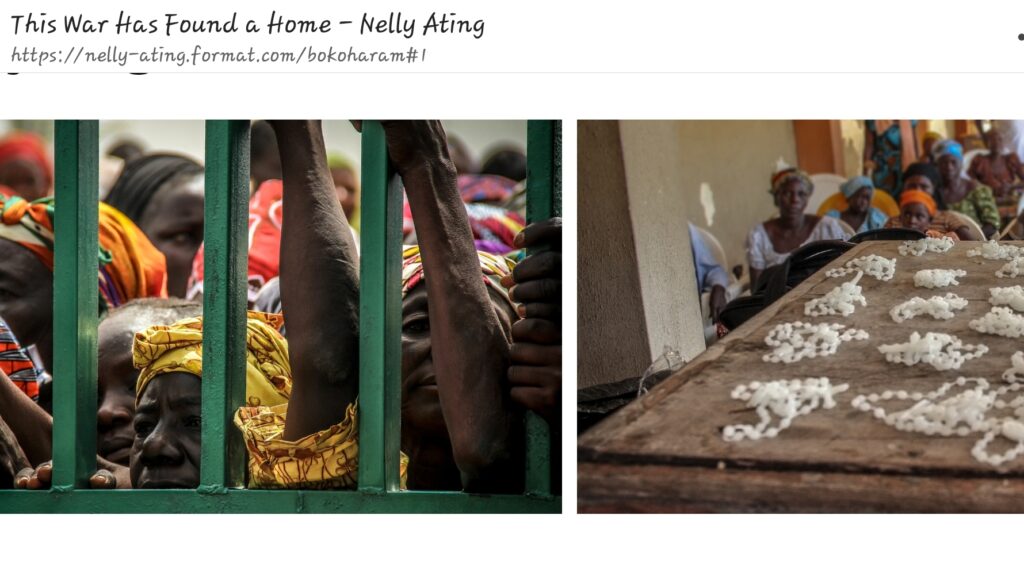

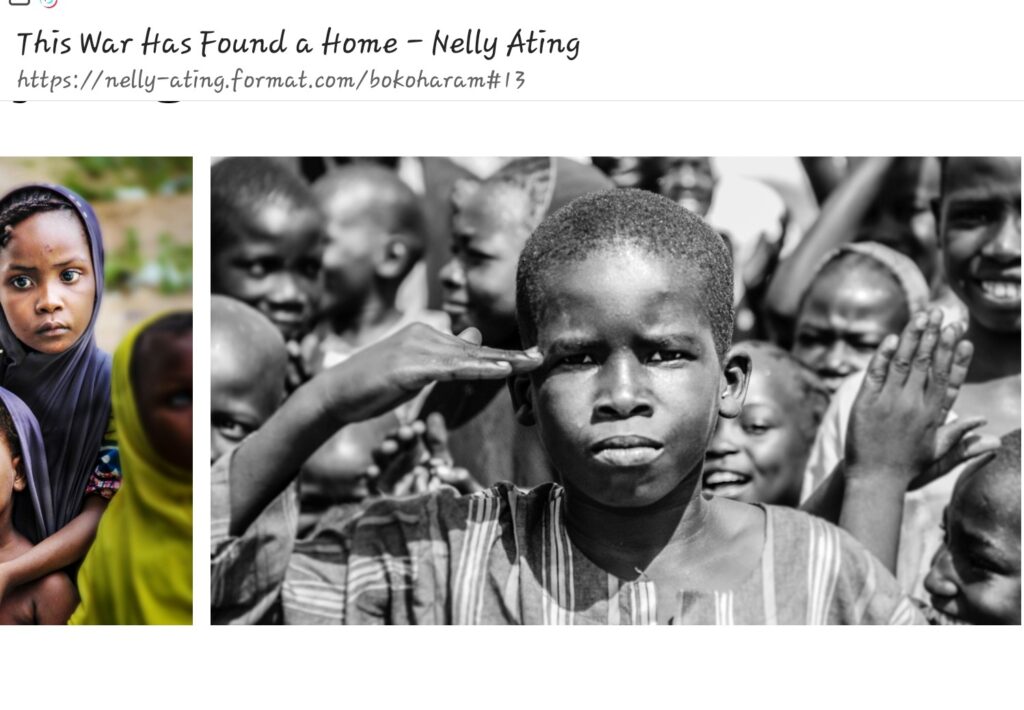

Outside of my documentation of women and children affected by Nigeria’s insurgency. I began using self-portrait as a form to bring issues that borders around social justice and gendered norms into conversations. I am now more tilted towards historical projects. I can’t say one particular project, as all my projects have worked for different audiences.

What career projection are you setting up for yourself you intend to meet up?

Supporting African photographers with knowledge on ethics and providing more nuanced work.

What training programmes or short courses have you attended, which you applied to the job that made the most impact for you?

Pursuing a PhD has to be the best career decision I have made.

What informed your move to the UK?

I left to pursue a career in academics.

Before you left for the UK, while in Nigeria, was photography a highly demanded skill in the Media space? Did you feel you were under appreciated for your talent, expertise?

I worked with mainly non-profit organisations and pitched to international desks. I never felt unappreciated. I knew art was subjective, and not everyone would like my work. I focused on the target audience that connected with my style of storytelling. To every young photographer, it is ok not to play to the tune of everyone as long as you find pleasure and passion, keep going

Why was covering the ENDSARS protest important for you

ENDSARS was a social movement organically mobilised online. I knew history was about to be made, and I found myself documenting the culture ENDSARS bred. Young Nigerian creatives performed a certain level of resistance that was unique to our people. Like most social movements, they don’t fade. They morph into something bigger. Watching Nigeria’s political space, ENDSARS did birth a new fire amongst young people. It has taken a root in our system. My documentation of ENDSARS was a contribution to using storytelling as a form of resistance.

For once in Nigeria, the youth united against tribe, religion, and ethnicity to demand change. or years, the Nigerian police unit known as the Special Anti-Robbery Squad (SARS)—designed for tactical undercover operations to take down criminals—has extorted, harassed, and killed young people who happen to use expensive phones and drive flashy cars. The plainclothes police also target those who sport dreadlocks and tattoos.

Nigerian youths leveraged art and culture as an expression to fight social injustice. These young people were protesting in the best way that defined their identity. While many may have condemned the laxity at which protesters deployed in taking their stand. It was actually interesting the various talents, especially the painters, rappers, dancers, and comedians, that were discovered through the EndSARS protest.

Why does the use of photography in activism matter to you? Why do you tell your stories that way and what impact has it made that continues to inspire you to use this medium or approach?

There’s a branch out of human rights visual culture that has historically used photographs to attract public pressure on issues peculiar to their mission. Photographs are sometimes used to amplify a particular cause. However, in activism, portraits are mainly used in a case where an activist has been detained. Photographs of these activists circulate through a hybrid media sphere that sometimes have a life beyond the activist even when they are released. At the same time, not all images have the same power to drive social change. It has continued to challenge how I approach photography in activism as I pay attention to stories that matter within my community.

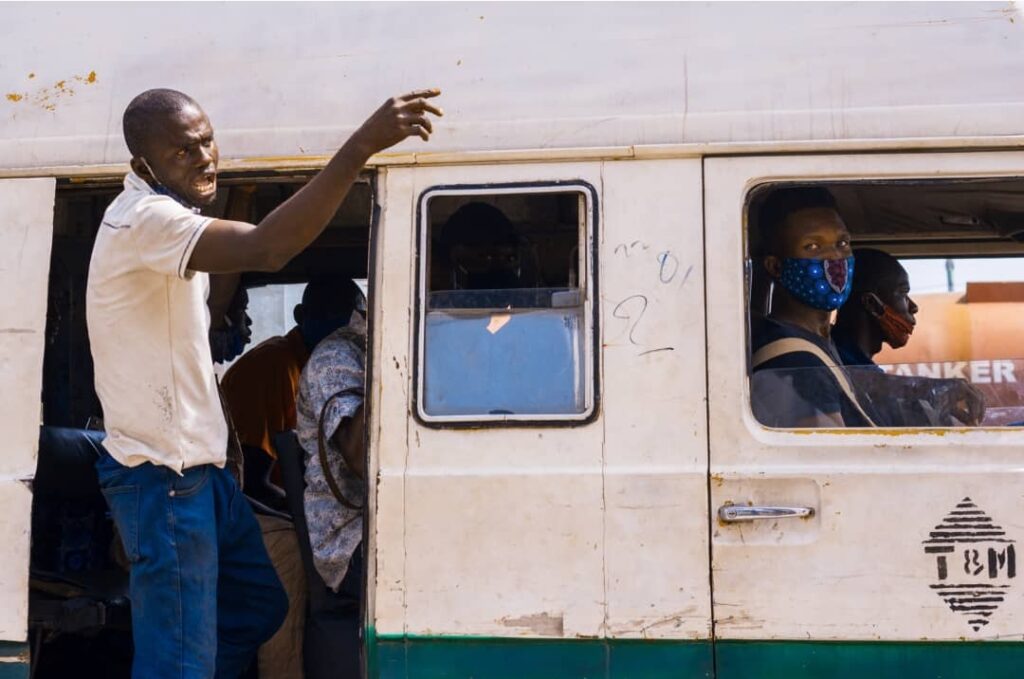

The photograph of Lagos commuters was captured under lockdown in 2020. Barely a few weeks after the Buhari government announced lockdown, Lagos transportation was hugely affected. It was most difficult for commuters who were told to sit sparsely, and for others, the lockdown rule meant sitting at home. It was fascinating to see how a city with over 20 million people and poor transportation services managed under a raging virus.

Any suggestions you’ll give to media owners or heads of media business to help boost morale, effectiveness?

I understand that Nigeria is not the safest place for press freedom. I have never worked in any media house, so I would not know what affects them. But, here’s what I would say: look after yourself. Less internalising of issues that relate to your beat and more time to recuperate.

If you were to reimagine you career, what will you do differently?

If I were to reimagine my career differently, I would trust the process and embrace the slow growth. I will also address the photojournalism landscape.

How would you describe the media landscape and the disruptions that will affect the field of photography?

The entrance of AI into photography, it also pushes African photographers into a more marginalised corner as that dominance may interfere with commissioning work on how local photographers tell indigenous stories. However, this disruption also means that the dominant gaze has also been replicated as machine gaze. It is obvious with how machines paint humans, especially black bodies, as plastic. The media landscape has always survived disruption by pivoting. With this new age of disinformation and photo manipulation, the media space will continue to survive.

Nelly Ating, Photo Journalist: Photographs are sometimes used to amplify a particular cause. However in activism, portraits are mainly used in a case where an activist has been detained. Photographs of these activists circulate through a hybrid media sphere that sometimes have a life beyond the activist even when they are released. At the same time, not all images have the same power to drive social change. It has continued to challenge how I approach photography in activism as I pay attention to stories that matter within my community.

Nelly Ating, Photo Journalist: There’s a branch out of human rights visual culture that has historically used photographs to attract public pressure on issues peculiar to their mission.

How and what can women in media begin to do differently and better to hold their own space within the media industry?

Keep developing our skills to meet the needs of our time. We need more women in academia too.

Tell us about any of your accomplishments that inspire you to do more?

Presenting at NYU Global Artist Symposium last year.

What tips in personal development, career pursuit, network strategies, and wealth creation would you advise other women in media, including men, to tap into?

Pitching to international desk. Pursing personal projects.

In the next 3-5 years, where do you see yourself?

Teaching, mentoring, and drafting policies.

Is taking photography the way you unwind?

IT. IS. EVERYTHING! (she bursts into an infectious gale of laughter). I couldn’t help laughing out loud myself.

Written by ERU.

Comments