Infant Mortality: Malaria’s Deadly Contribution in Sub-Saharan Africa

By Precious Nwonu

Malaria is a serious and sometimes life-threatening disease caused by Plasmodium parasites. These parasites are transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes.

Globally, infant mortality—defined as the death of a child before their first birthday—has significantly declined over the past few decades, thanks to improvements in healthcare, vaccination, sanitation, and nutrition.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the global infant mortality rate dropped from 65 deaths per 1,000 live births in 1990 to around 26 per 1,000 in 2023. However, the burden is not evenly shared. Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia continue to record the highest infant mortality rates, due to limited access to quality healthcare, poor maternal health, and preventable infectious diseases.

Sub Saharan Africa

Country Infant Mortality Rate (%)

Somalia (85.1)

Central African Republic (81.7)

Equatorial Guinea (77.9)

Sierra Leone (72.3)

Niger (65.5)

Chad (64.0)

South Sudan (61.6)

Mozambique (59.8)

DR Congo (59.1)

Mali (59.0)

Angola (57.2)

Liberia (56.1)

Comoros (56.0)

Nigeria (55.2)

These countries represent the worst infant mortality rates globally—with many exceeding 50 deaths per 1,000 live births.

South Asia

Country Infant Mortality Rate (%)

Pakistan (49 )

Afghanistan (46)

India (23–27)

Bangladesh (24–29)

Nepal (24–28)

Bhutan (19–26 )

Sri Lanka (6 )

Source: TheGlobalEconomy.com

In malaria-endemic regions, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, malaria remains a major contributor to infant deaths. Infants are especially vulnerable due to their immature immune systems. Malaria during pregnancy can also result in low birth weight, preterm delivery, and neonatal death. In these regions, the combination of malaria and weak health infrastructure often leads to delayed diagnosis and inadequate treatment, increasing the risk of fatal outcomes. Despite ongoing efforts through insecticide-treated nets, intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy, and rapid diagnostics, malaria still plays a significant role in preventable infant mortality in these high-risk areas.

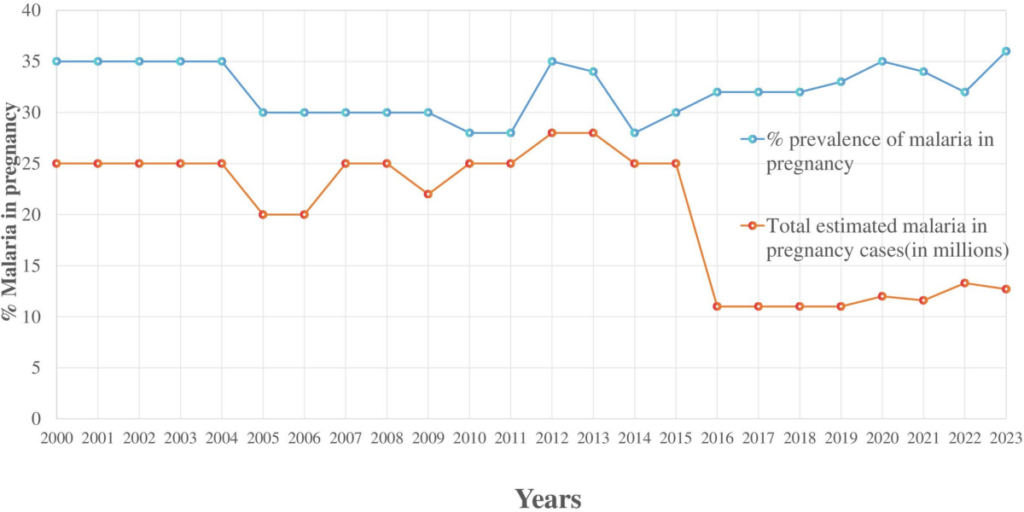

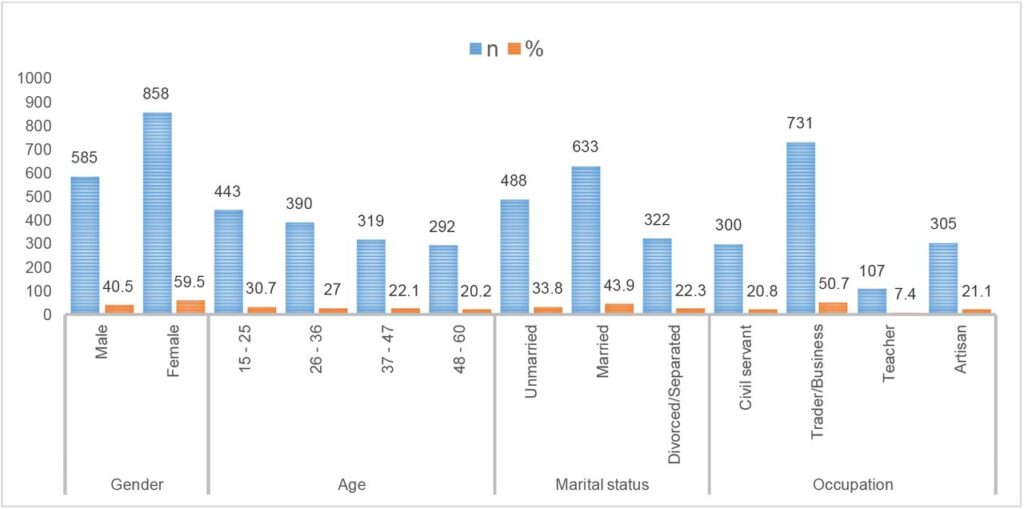

Sub-Sahara Africa accounts for approximately 94% of all malaria cases and deaths worldwide, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). In Nigeria, as of 2020, about 69.6% of pregnant women attended antenatal care (ANC) at least once with skilled health personnel. Despite this, child mortality rates remain high. According to the 2021 MICS/NICS, the neonatal mortality rate was 34 per 1,000 live births, the infant mortality rate was 63 per 1,000, and under-five mortality reached 102 per 1,000 live births, with neonatal deaths contributing a significant portion. Efforts to prevent malaria during pregnancy have seen limited success—only 6% of women received three or more doses of the preventive treatment SP (Fansidar) in 2010, and although coverage improved to about 44% by 2023, it still remains modest nationwide.

The disease places immense pressure on fragile health systems, drains economic resources, and contributes to cycles of poverty and underdevelopment. Children under five years old are especially vulnerable, often experiencing severe complications due to their undeveloped immune systems. Malaria also affects maternal health, increasing the risk of miscarriage, stillbirth, and low birth weight, which can lead to infant death.

According to Sarfo et al. (2025) in their study titled “Malaria Amongst Children Under Five in Sub-Saharan Africa,” key risk factors for malaria in children under five (UN5) include low or no formal education, poverty or low household income, and residence in rural areas. The evidence regarding age and malnutrition as risk factors remains inconsistent and inconclusive. Additionally, poor housing conditions, lack of electricity in rural areas, and limited access to clean water further increase the vulnerability of UN5 to malaria. However, the study notes that health education and promotion interventions have played a significant role in reducing the malaria burden in this population across sub-Saharan Africa.

Infant mortality due to malaria is particularly alarming. In 2022, WHO estimated that out of the 608,000 global malaria deaths, around 80% were children under the age of five, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. This translates to a child dying from malaria nearly every minute. Despite significant progress in malaria prevention through insecticide-treated nets, indoor spraying, and preventive treatments, millions of infants remain at risk due to gaps in healthcare access, poor living conditions, and limited awareness. The high burden of malaria-related infant deaths highlights the urgent need for sustained global investments in prevention, early diagnosis, treatment, and community health education in malaria-endemic regions.

Malaria is primarily transmitted to humans through the bite of infected female Anopheles mosquitoes, which are most active between dusk and dawn. When an infected mosquito bites a person, it injects the Plasmodium parasites into the bloodstream. These parasites travel to the liver, where they mature and multiply before re-entering the bloodstream to infect red blood cells. Among the five species that infect humans, Plasmodium falciparum is the most dangerous, responsible for the majority of severe cases and deaths, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa.

Infants are particularly vulnerable to malaria for several reasons. Their immune systems are not fully developed, making it harder for them to fight off infections, including malaria. Infants born to mothers who have not developed adequate immunity to malaria are at a higher risk of infection and severe illness. Additionally, malaria can be transmitted from mother to child during pregnancy or delivery, increasing the chances of infection in newborns. Factors such as malnutrition, poor access to healthcare, and inadequate use of preventive measures (like mosquito nets) further expose infants to the disease and its complications.

A study conducted by Oranuka et al. (2023) titled “Placental Malaria and Its Relationship with Neonatal Birth Weight among Primigravidae” revealed that 38.4% of participants had placental malaria. Among those with positive placental parasitemia, 49.6% were diagnosed with chronic infections, 36.5% with acute infections, and 13.9% with past infections.

Symptoms of malaria in infants can be more severe and harder to detect than in older children or adults. Common signs include a high fever, irritability, poor feeding, and lethargy. As the disease progresses, infants may develop severe anemia due to the destruction of red blood cells, convulsions, respiratory distress, or even coma. If not diagnosed and treated promptly, these symptoms can rapidly worsen and lead to death. Early recognition and treatment, as well as preventive strategies like insecticide-treated nets and preventive medication for pregnant women, are essential to protecting infants from the deadly consequences of malaria.

The burden of malaria in endemic countries remains alarmingly high, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where the disease poses a major threat to public health, economic development, and child survival. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report 2023, there were an estimated 249 million malaria cases globally in 2022, with 94% (approximately 234 million) of those cases occurring in the WHO African Region. This region also accounted for 95% of global malaria deaths, underlining the disproportionate impact of the disease in low-income, tropical countries.

Children under five bear the greatest burden. In 2022, approximately 580,000 malaria deaths were recorded globally, of which about 80% (460,000 deaths) were among children under the age of five, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa (WHO, 2023). According to UNICEF, malaria is one of the top causes of death for young children in the region, killing one child nearly every minute. Countries like Nigeria, Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and Mozambique are among the hardest hit, together accounting for over half of all malaria deaths worldwide.

Findings from Garrison et al. (2023) in their study titled “The Effects of Malaria in Pregnancy on Neurocognitive Development in Children at 1 and 6 Years of Age in Benin” revealed that out of 493 pregnant women, 196 (40%) experienced malaria infection at least once, with 121 (31%) diagnosed with placental malaria through qPCR testing.

Malaria also significantly impacts maternal and neonatal health. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that malaria during pregnancy can lead to low birth weight, preterm birth, and stillbirth, all of which increase the risk of infant mortality. In malaria-endemic countries, up to 10,000 maternal deaths and 200,000 neonatal deaths are linked to malaria each year (CDC, 2022). These statistics underscore the urgent need for sustained malaria control efforts, including expanded access to insecticide-treated bed nets, preventive treatment during pregnancy, effective diagnosis, and timely treatment.

According to Greenwood, B.M. et al. (1991) Malaria transmission is highly influenced by seasonal patterns, particularly in tropical and subtropical regions where rainy seasons create ideal breeding conditions for the Anopheles mosquito. These seasonal spikes often lead to surges in malaria cases and deaths, with infants being among the most affected. In many malaria-endemic countries—especially in sub-Saharan Africa—malaria transmission peaks shortly after the start of the rainy season due to increased mosquito activity and standing water that facilitates breeding.

During these high-transmission periods, infant death rates also tend to rise, as the surge in malaria cases overwhelms already fragile healthcare systems. Infants under one year of age are at greatest risk because of their underdeveloped immunity and the difficulty in detecting symptoms early. Studies show that malaria-related hospital admissions and deaths among infants significantly increase during the rainy season.

For example, a study in Gambia (Greenwood et al., 1991) found that infant mortality was nearly twice as high during the malaria season compared to the dry season. Similarly, research from Nigeria and Mozambique reports higher infant case fatality rates during peak transmission months.

Nigeria continues to carry the highest global burden of malaria, accounting for approximately 26–27% of global cases and nearly 40% of malaria-related deaths among children under five as of 2023. The prevalence of malaria among children aged 6 to 59 months remains alarmingly high nationwide, with a reported rate of 23.3% according to the NCDC’s 2024 demographic report. In 2025, Kebbi State recorded the highest prevalence among young children at 49%. A 2024 study published in BMC Pediatrics further emphasized the severity of the issue, revealing that around 80% of malaria deaths in the region occurred in children under five, underscoring their extreme vulnerability.

Combating malaria in infants presents numerous challenges, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, where the burden of the disease is highest. One of the foremost challenges is limited access to healthcare services, particularly in rural and hard-to-reach areas. Infants often do not receive timely diagnosis or treatment due to a shortage of trained health workers, poor infrastructure, and lack of diagnostic tools like rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs).

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) World Malaria Report (2023), delays in treatment significantly increase the risk of complications and death in infants, who can deteriorate quickly if infected with malaria. Furthermore, many caregivers may not recognize early symptoms of malaria in infants—such as poor feeding, fever, or irritability—which often resemble symptoms of other common childhood illnesses.

Another major challenge is the inadequate use of preventive measures, such as insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs) and intermittent preventive treatment for pregnant women (IPTp). Many households either do not have access to bed nets or do not use them consistently. A 2023 UNICEF report noted that while ITN coverage has improved in some areas, usage among children under five remains suboptimal.

In addition, low uptake of IPTp during pregnancy means many babies are born with low immunity or already infected, placing them at higher risk of severe malaria. Social and economic factors—like poverty, low maternal education, and cultural practices—further hinder the effective implementation of malaria prevention strategies.

The limited rollout of malaria vaccines also contributes to the challenge. While WHO-approved vaccines such as RTS,S and R21/Matrix-M offer hope, access remains limited due to cost, supply constraints, and the need for multiple doses over time.

R21/Matrix-M — a malaria vaccine developed by Oxford University and manufactured by the Serum Institute of India — was provisionally approved in April 2023 and integrated into Nigeria’s routine immunisation schedule in December 2024, beginning with pilot rollouts in Kebbi and Bayelsa states.

According to Gavi (2024) and WHO, full protection requires four or more doses starting at five months of age—yet ensuring infants complete the full vaccination schedule is difficult in many low-resource settings.

Vaccine hesitancy and weak health system monitoring also hinder progress. Addressing these challenges requires strengthening health systems, increasing funding, and promoting community-based approaches that support both prevention and early treatment of malaria in infants.

In October 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially certified Egypt as malaria-free, marking it the third country in the Eastern Mediterranean and the 44th globally to interrupt local transmission for over three years.

To effectively combat malaria in infants, strengthening access to early diagnosis and treatment is crucial. Governments and health organizations should prioritize the availability of rapid diagnostic tests (RDTs) and artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) at the community level, especially in rural and underserved areas. Community health workers should be trained and equipped to recognize symptoms in infants and provide prompt treatment. Integrating malaria care into routine child health services—including immunisation visits—can help reach more infants and ensure timely intervention.

Scaling up preventive strategies is another key priority. This includes the widespread distribution and proper use of insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs), particularly targeting households with pregnant women and infants. Increasing coverage of intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) is vital to reduce the risk of congenital malaria and improve birth outcomes.

The 2024 State of Health of the Nation report highlights that, despite ongoing efforts—including the use of insecticide-treated bed nets, rapid diagnostic testing, and treatment with artemisinin-based combination therapies—the global malaria burden remains high, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In malaria-endemic countries like Nigeria, case numbers fluctuate seasonally, with spikes commonly observed during the rainy season. The continued prevalence of malaria is fueled by multiple challenges, such as poor access to healthcare services, emerging drug resistance, and gaps in the effectiveness of control programs. To address these issues, it is essential for governments and health partners to scale up both preventive and treatment initiatives. Integrating malaria interventions with broader public health strategies, such as maternal care and immunization programs, also offers a valuable opportunity to reduce the disease’s impact more effectively.

The rollout of malaria vaccines like RTS,S and R21 should be accelerated and integrated into national immunisation schedules, ensuring infants complete the full vaccine course. To support this, strong health education campaigns are needed to address vaccine hesitancy and improve community trust in malaria prevention tools. As of April 2025, Nigeria is one of 20 African countries offering malaria vaccines (either R21 or RTS,S) through routine immunization, supported by Gavi and the WHO

Sustained political commitment and investment are essential. Governments, in collaboration with international partners such as WHO, UNICEF, and Gavi, must commit to long-term funding and policy support for malaria control programs. Egypt’s century-long efforts—ranging from vector control and free healthcare access to integrated surveillance and cross-border collaborations—demonstrate that sustained political will and strong health systems can achieve malaria elimination.

Strengthening surveillance systems, improving supply chains for essential commodities, and leveraging technology for disease tracking will enhance program effectiveness. With focused action, it is possible to significantly reduce—and eventually eliminate—malaria deaths in infants and achieve global health targets for child survival.

Comments