Co-infections Complicate HIV Treatment: TB, Hepatitis, Pregnancy, and More

by Precious Nwonu

HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus) is a virus that attacks the body’s immune system — the part that fights off infections. If not treated, it can lead to AIDS (Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome), which is the final and most serious stage of HIV when the body becomes too weak to fight off diseases.

People living with HIV face a significantly higher risk of serious co-infections—most notably tuberculosis (TB) and hepatitis—which greatly worsen health outcomes. Co-infection means having two or more infections in the body at the same time.

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis that most often attacks the lungs—though it can affect other parts of the body like the kidneys, spine, or brain. It’s spread when a person with active (lung) TB coughs, sneezes, laughs, or breathes out droplets containing the bacteria, which others then inhale. A very small number of inhaled bacteria can lead to infection.

TB exists in two main forms; Latent TB infection —The bacteria live in the body without causing symptoms. People in this stage aren’t contagious, but about 5–10% will develop active TB at some point in their lives. TB can stay “quiet” in the body for years without causing illness (this is called latent TB)

While the second one Active TB disease — it occurs when the body’s immune system can’t control the bacteria. Symptoms include a cough lasting more than three weeks, chest pain, fever, weight loss, night sweats, and fatigue. Without treatment, active TB can kill and is contagious.

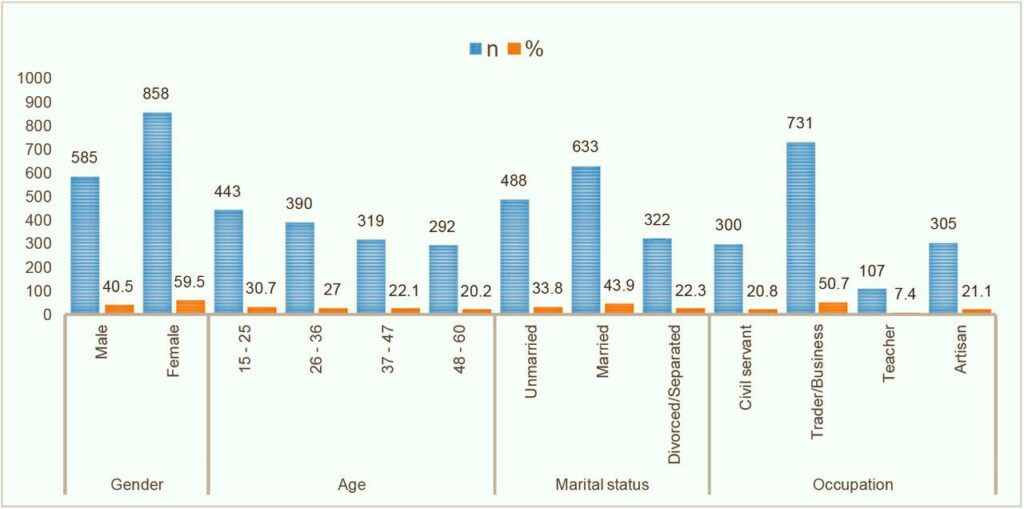

In a study by Nwoga et al. (2024) on the prevalence and determinants of TB/HIV coinfection in Enugu State, Nigeria, all 483 patients treated for TB between 2018 and 2022 were screened for HIV. Among them, 29.0% were found to have TB/HIV coinfection, with the highest prevalence recorded in 2021 (27.1%). Logistic regression analysis revealed that TB/HIV coinfection was significantly more likely among traders (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] 4.932; 95% CI: 1.364–17.839) and students (AOR 2.772; 95% CI: 1.014–7.577). Conversely, individuals diagnosed in 2022 (AOR 0.514; 95% CI: 0.272–0.969) and those residing in urban areas (AOR 0.594; 95% CI: 0.372–0.949) had significantly lower odds of coinfection.

The bar chart displays regional co-infection prevalence across Nigeria, illustrating the significant burden, especially in the North Central region (~34%). This national picture is further supported by consistent facility-based rates (~20–30%) in Enugu, Ogun, and Anambra states

These co-infections are common because HIV weakens the immune system, making it harder for the body to protect itself. When a person has both HIV and another infection, it can make them sicker, speed up the damage caused by HIV, and increase the risk of death if not treated early and properly.

For example, individuals with HIV are 15–22 times more likely to develop active TB than those without HIV, and TB remains the leading cause of death among people with HIV. Common symptoms of TB include a cough that won’t go away, weight loss, night sweats, and fever. In 2023 alone, approximately 161,000 people died of HIV-associated TB, while just under 60% of TB patients co-infected with HIV received antiretroviral therapy.

According to findings by Sossen et al. (2025), HIV-associated tuberculosis (HIV-TB) is linked to significantly higher mortality rates. In 2023, about 24% of the 660,000 individuals with both TB and HIV died, compared to 11% of TB patients without HIV. HIV remains a major driver of the persistently high TB incidence in many countries, especially within the World Health Organization (WHO) Africa Region. Globally, TB is also the leading cause of hospitalization among people living with HIV.

Globally, around 2.2 million people have both HIV and hepatitis C, with HIV-positive individuals being 6 times more likely to have hepatitis C virus (HCV) than those without HIV. These co-infections accelerate disease progression—co-infected patients are more likely to suffer liver cirrhosis, cancer, and treatment complications. These other infections can become more serious and harder to treat when a person already has HIV, because the body is not strong enough to fight them off properly.

In 2024, Nasarawa State recorded 8,190 cases of Tuberculosis (TB), with 35 residents reportedly losing their lives to the disease, as disclosed by the State Ministry of Health. The rise in cases—from 7,275 in 2023—was accompanied by a concerning rate of co-infection, with about 21% of TB patients also living with HIV. The deaths were largely linked to the severity of the infections.

A 2024 meta-analysis of 80 Nigerian studies involving 44,508 participants reported an overall HIV–TB co-infection rate of 25.8%, with the North Central region recording the highest prevalence at 34.3%, while the South-East had the lowest at 19.3%. In Enugu State, hospital records from 2018 to 2022 revealed that 29.0% of TB patients were also HIV-positive. Similarly, a 2023 survey conducted in Ogun State’s DOTS clinics, covering data from 2015 to 2019, found a co-infection rate of 22.5% among 726 TB patients. In Anambra State, data from 2013 to 2017 indicated an average co-infection rate of 20%, with yearly figures ranging from 13.2% in 2013 to 23.8% in 2014.

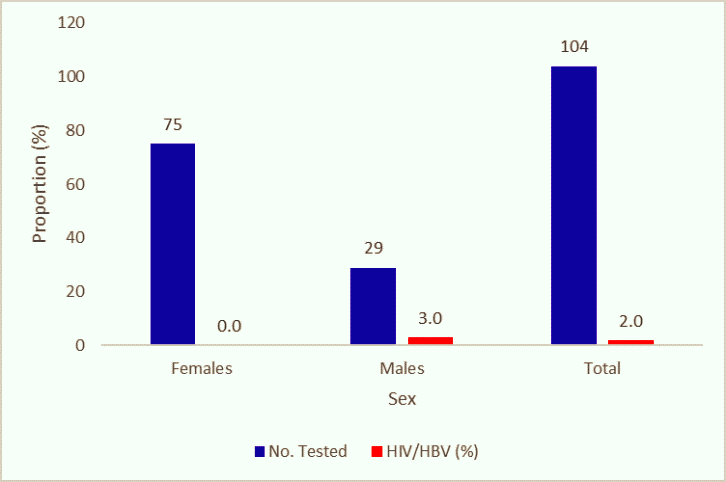

Blue/Red bars Highlights HBV (~13%) and HCV (~4%) among HIV-positive patients in Jos.

Hepatitis B and C are viruses that attack the liver and spread in the same ways as HIV—through blood contact, shared needles, and sexual activity.

According to World Health Organisation (WHO) “Hepatitis is an inflammation of the liver. The condition can be self-limiting or can progress to fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis or liver cancer. Hepatitis viruses are the most common cause of hepatitis, but other infections, toxic substances (e.g. alcohol, certain drugs), and autoimmune diseases can also cause hepatitis.” There are different types of viral hepatitis—mainly hepatitis A, B, C, D, and E. Among these, hepatitis B and C are the most serious because they can lead to long-term (chronic) liver problems like liver damage, liver failure, or liver cancer. These types often spread through contact with infected blood, sharing needles, or unprotected sex.

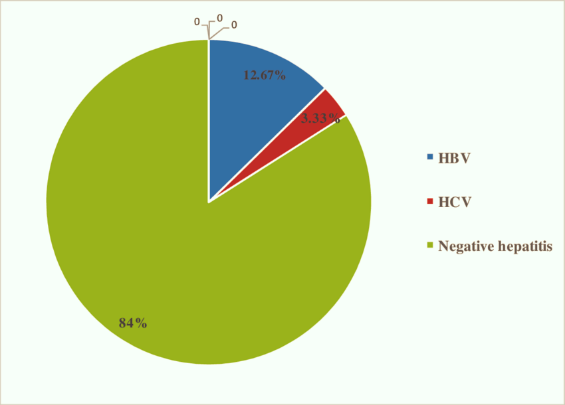

Recent data from various Nigerian health institutions reveal concerning trends in HIV and viral hepatitis co-infections. In 2023, a study at a Jos tertiary hospital involving 2,224 HIV-positive individuals found co-infection rates of 13.4% for HIV/HBV, 4.3% for HIV/HCV, and 0.31% for triple infection (HIV/HBV/HCV). National trends from the NCDC (1990–2021) indicate a decline in HBV positivity among HIV test clients—from 12% in 2019 to 4% in 2021—and a similar drop in HCV positivity from 21% to 3%.In a recent assessment at a rural hospital in northern Nigeria, HIV/HBV co-infection was 6.0%, HIV/HCV was 14.6%, and triple infection reached 1.1%. Among pediatric cases in Lagos, HBV prevalence was 5.3% in HIV-infected children compared to 4.8% in HIV-naïve controls, with similar anti-HBc and HCV rates across both groups. According to the 2018 Nigeria AIDS Indicator and Impact Survey (NAIIS), national seroprevalence stood at 7.6% for HBV and 1.7% for HCV, with HBV rates ranging between 5% and 13% across regions.

About 7.6% of people living with HIV also carry hepatitis B (roughly 2.7 million globally), with the highest burden in sub‑Saharan Africa. For hepatitis C, around 2–15% of HIV-positive individuals are co-infected, and as many as 20% in some groups. This overlap is due to shared transmission routes and common risk behaviors.

Findings from a research conducted in Northern Nigeria by Adesegun et al. (2020) revealed that out of 281 individuals who participated in the study, the prevalence of Hepatitis B co-infection, Hepatitis C co-infection, and triple infection (HIV, HBV, and HCV) was 6.0%, 14.6%, and 1.1% respectively. When analyzed using the Chi-square test, none of the socio-demographic factors, WHO Clinical Stage, or viral suppression showed a significant link with Hepatitis B co-infection. Interestingly, marital status was found to have a significant association with Hepatitis C co-infection, while the level of education was significantly related to the occurrence of triple infection (p < 0.05). However, logistic regression modeling did not identify any statistically significant predictors for these co-infections.

Having both HIV and hepatitis significantly raises the chance of serious liver problems. Research shows HIV speeds up liver damage in hepatitis patients, causing faster fibrosis (scarring), cirrhosis, and a higher risk of liver cancer. (https://www.verywellhealth.com/hepatitis-7484113) For example, HIV/HBV co-infected people are over four times more likely to develop cirrhosis and face more aggressive liver cancer.

A cross-sectional study led by Meseret Ayelign et al. in Northwest Ethiopia involved 81 participants, of whom 56.8% were female and 67.9% lived in urban areas. The study found that the overall prevalence of hepatitis co-infection among the participants was 21% (95% CI: 17%, 23%). Specifically, the rate of HBV/HIV co-infection was 13.5% (95% CI: 10.5%, 16.5%), while HCV/HIV co-infection stood at 8.6% (95% CI: 5.6%, 11.6%). Importantly, the careful use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) was identified as a protective factor against hepatitis infection, with an odds ratio of 0.01 (0.00, 0.213).

Treating co-infections requires a combined approach: antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV alongside special antiviral drugs for hepatitis. For hepatitis B, using medications like tenofovir as part of HIV treatment helps control both viruses . Hepatitis C can often be cured with direct-acting antivirals (DAAs), taken for 8–12 weeks and proving effective more than 95% of the time.

Apart from TB and Hepatitis B and C, people living with HIV can also be affected by other co-infections such as Human Papillomavirus (HPV), Herpes Simplex Virus (HSV), Cytomegalovirus (CMV), Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) and a whole lot of others.

People living with HIV are much more likely to have HPV. A 2025 review reports that 37% of HIV positive individuals carry HPV, compared to about 4% in those without. This infection can lead to cancers—especially cervical and anal cancers—up to six times more often in women with HIV, and anal cancer rates are also significantly higher in HIV positive men (https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/40172095/)

HSV causes cold sores or genital blisters, and those with HIV often experience more frequent and longer outbreaks. While precise global figures are less clear, experts warn that HSV can also make it easier for HIV to spread to others during outbreaks—showing a dangerous two way relationship between the infections.

In a 2025 study by Okon et al. titled Epidemiology and Co-infection Analysis Among HIV-Infected Individuals Presenting at a Teaching Hospital in Bayelsa State, Nigeria, a cross-sectional design was adopted. The study population comprised HIV-positive individuals receiving clinical care at the Niger Delta University Teaching Hospital (NDUTH), Bayelsa State. Blood samples were collected from 200 consenting participants for serological testing of cytomegalovirus (CMV), hepatitis B core antibody (HBc IgM), and herpes simplex virus types 1 and 2 (HSV-1 & HSV-2), using commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits. CMV IgG was detected in 169 samples (84.5%), indicating persistent CMV co-infection, while CMV IgM was found in 130 samples (65.0%), suggesting recent CMV infection. Additionally, HBc IgM was detected in 48 samples (24.0%), HSV IgG in 114 (57.0%), and HSV IgM in 79 (39.5%). Overall, 189 participants (94.5%) tested positive for at least one of the three viruses—CMV, HBV, or HSV.

Anaedobe and Ajani (2019), in their study on ‘Co-infection of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 (HSV-2) and HIV Among Pregnant Women in Ibadan, Nigeria,’ reported a seroprevalence of 33.3% (90 out of 270) for HSV-2 type-specific IgG, while HIV antibodies were detected in 19.63% (53 out of 270) of the participants. Among HSV-2-positive women, 38.8% (35 out of 90) were also co-infected with HIV, compared to 10% (18 out of 180) among HSV-2-negative women. The majority of HSV-2-positive women (62.2%, 56 out of 90) were in their second trimester, while 18.9% (17 out of 90) were in their third trimester.

Pie chart represents co-infection distribution in Kano teaching hospital: ~12% HBV, ~5% HCV in HIV cohort

CMV typically stays quiet but can become very serious in people with very weak immune systems, affecting the eyes, lungs, or gut. Meanwhile, PCP is a lung infection common in advanced HIV/AIDS—about 30–40% of PCP cases occur in people with HIV.

Historically, PCP affected up to 70–80% of people with untreated, advanced HIV and carried a 20–40% death rate. With HIV medicines and PCP prevention pills like TMP SMX, its rates have dropped sharply—now often under 1 case per 100 person years in regions like the U.S. and Europe.

People living with HIV should regularly get tested for infections like TB and hepatitis B or C because their weakened immune systems make it easier for other diseases to take hold. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), about 50% of people with HIV who start antiretroviral therapy also receive preventive treatment for TB. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) also recommends that every adult be tested at least once for hepatitis B—and more if they’re at high risk—to help catch infections early.

Between April 2022 and March 2023, CDC-backed NCDC progrmmes supported approximately 1.2 million people living with HIV (PLHIV) on antiretroviral therapy (ART), with 97% of them screened for tuberculosis (TB). During this period, 15,721 cases of TB/HIV co-infection were identified, and 99% of those affected were initiated on ART. In addition, 121,215 PLHIV began TB preventive treatment, with 98% successfully completing the therapy.

Having another infection can change when and how people start HIV treatment (ART). For example, someone with both HIV and active TB might need to treat TB first or adjust their HIV medicines so they don’t interact improperly. If someone has HIV and hepatitis B, doctors will pick an ART plan that can fight both viruses at the same time . These careful choices help prevent side effects and ensure both infections are controlled effectively.

To stay ahead of these infections, healthcare providers use blood tests (like liver or viral load checks), imaging (such as X-rays for lung health), and close monitoring of symptoms like chronic cough, fever, or fatigue. WHO emphasizes the use of fast molecular tests (such as GeneXpert for TB) along with newer urine tests to catch TB early in people with HIV. Regular check-ups and tracking help find problems early, making treatment more effective and improving health over time.

Recent evidence presented by Sossen et al. (2025) highlights that antiretroviral therapy, along with innovative TB preventive regimens, has contributed significantly to reducing TB incidence and enhancing survival outcomes. Diagnostic tools such as Xpert Ultra (Cepheid, USA) and the urine Determine™ TB LAM Antigen test (Abbott, USA) have also been linked to improved survival rates among individuals co-infected with HIV and TB. Despite these advancements, critical knowledge gaps remain — particularly concerning the natural progression of TB in people with HIV (PWH), the best diagnostic strategies for detecting TB and drug resistance (especially using non-sputum samples), and the long-term effects of TB in PWH.

Starting antiretroviral therapy (ART) early is one of the best ways to protect people with HIV from getting more infections. According to WHO, more than 30 million people were on ART in 2023, and 77% of those with HIV are now receiving it. ART not only suppresses the HIV virus but also helps keep the immune system strong, which reduces the chance of infections like tuberculosis (TB) by up to 84% . This early treatment approach, often called “treatment as prevention,” is a WHO-backed strategy that can greatly improve health and reduce transmission.

In addition to ART, people with HIV should get vaccinations and preventive medicines to stay healthy. WHO strongly recommends Hepatitis B vaccination and TB prevention therapy (TB prophylaxis) for those with HIV-infection. Preventive shots and medicines help stop co-infections before they start. Plus, living a healthy lifestyle with good nutrition, clean water, proper hygiene, and avoiding injection drug use can make a big difference in lowering the chance of co-infections.

Raza et al. (2025), in their study on a mathematical framework for HIV and TB co-infection dynamics, noted that while there is currently no definitive vaccine or cure for HIV, antiretroviral therapy (ART) remains effective in slowing disease progression and preventing associated complications.

When healthcare providers treat HIV and other illnesses together, people do much better. WHO’s global HIV programme encourages integrated care systems that include HIV, TB, hepatitis, and other infections in one health package. These programmes combine testing, prevention, treatment, nutrition, and hygiene into one streamlined service. Countries that provide combined care see better health results—fewer infections, earlier detection, and improved overall wellbeing. With this approach, people with HIV can live longer, healthier lives while reducing the spread of co-infections.

Comments