Stigma and Silence: How Cultural Perceptions of TB Affect Treatment Seeking

By Precious Nwonu

In a small village in northern Nigeria, a young mother concealed her baby’s malaria diagnosis from neighbors out of fear and stigma. “They’ll say I’m careless or cursed,” she whispered to a health worker. This silence proved deadly—by the time the child was rushed to the clinic, it was too late.

Such tragic outcomes are not rare. In 2022 alone, over 450,000 children under five died from malaria, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the World Health Organization. Behind these numbers are stories of missed diagnoses, fear, poverty, and health systems stretched beyond capacity. These realities highlight the urgent need to not just treat malaria, but also confront the social, cultural, and structural barriers that keep parents from seeking help until it’s too late.

The Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS), in collaboration with the National TB & Leprosy Control Programme, reported that Nigeria recorded its highest-ever tuberculosis (TB) case notification in 2023, with 371,019 cases documented. Despite this progress in detection, findings from the 2023 National Health Facility Survey reveal that only 16.2% of health facilities across the country offer TB diagnosis and treatment services. There are significant regional disparities in service availability, with the South-West zone leading at 20.5% facility coverage, while the South-East trails behind at just 8.9%.

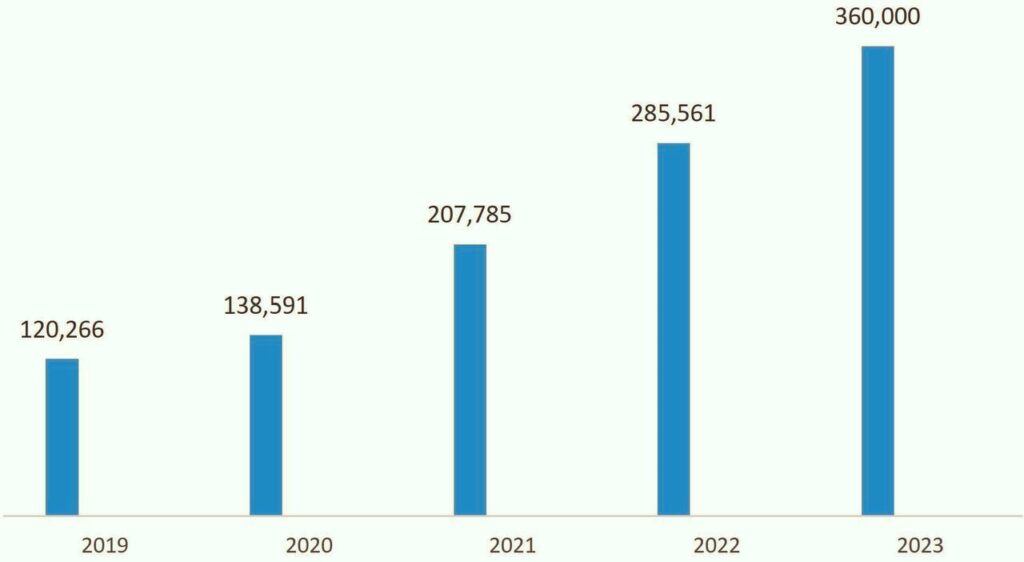

TB case notifications from 2021 to 2023.

Source: Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS), in collaboration with the National TB & Leprosy Control Programme.

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the world’s leading infectious disease killers, especially in low- and middle-income countries. It is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis and primarily affects the lungs, spreading through the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes. Despite being preventable and curable, TB continues to pose a major global health threat.

Mukerji and Turan (2019), in their study titled “Exploring Manifestations of TB-Related Stigma Experienced by Women in Kolkata, India,” highlighted that TB-related stigma primarily manifested through social isolation, avoidance due to fear of contagion, gossip, verbal abuse, failed marriage prospects, and neglect from family members. The women also reported that stigma led to non-disclosure of their TB status, feelings of guilt, and mental health challenges, including suicidal thoughts.

According to the World Health Organization (2023), an estimated 10.6 million people fell ill with TB in 2022, and about 1.3 million died, with the vast majority of deaths occurring in developing nations. Over 95% of TB cases and deaths are reported in low- and middle-income countries, with the highest burdens found in regions such as sub-Saharan Africa, South-East Asia, and the Western Pacific. TB disproportionately affects vulnerable populations—especially those with HIV, malnutrition, or poor living conditions—underscoring the need for focused intervention and global solidarity. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2023).

This article explores how stigma and cultural beliefs surrounding tuberculosis (TB) discourage individuals—especially in low- and middle-income countries—from seeking timely diagnosis and treatment. Despite medical advances, fear of discrimination, social rejection, and deeply rooted misconceptions about TB continue to drive people to hide their symptoms, delay care, or avoid treatment altogether. Understanding and addressing these barriers is crucial to reducing TB transmission, improving health outcomes, and ultimately ending the TB epidemic.

In the context of health and illness, stigma refers to the negative attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors directed toward individuals who are affected by a particular disease. It often stems from fear, misinformation, or cultural norms, and leads to people being shamed, rejected, or discriminated against because of their health condition. In the case of diseases like tuberculosis (TB), stigma can cause individuals to hide their illness, delay seeking care, or isolate themselves—ultimately worsening their health and contributing to the spread of the disease.

Unlike some diseases that may be associated with lifestyle choices—such as HIV—TB stigma often stems from the belief that it is easily spread through casual contact, which leads people to isolate or avoid anyone known to have it. This fear can be especially strong in crowded communities where misinformation spreads quickly and education about TB is limited.

A study by Cremers et al. (2015) conducted in urban Zambia found that out of 300 patients, 138 described their perceptions and attitudes toward TB, with 113 (82%) reporting experiences of stigma.

While HIV stigma is often linked to moral judgment, sexuality, or perceived promiscuity, TB stigma is more closely tied to poverty, poor hygiene, or weakness, making it harder for people in affected areas to seek care without being labeled or rejected. In many cases, TB and HIV co-infection creates a double burden of stigma, leading to deeper isolation and worse health outcomes. Studies have shown that people with TB often delay diagnosis and treatment out of fear of being ostracized, losing their job, or being treated differently by friends and family.

According to a 2021 study published in BMJ Global Health, stigma remains one of the key barriers to ending the TB epidemic, especially in countries like India, Nigeria, and South Africa where TB is common but widely misunderstood.

The World Health Organization has also identified TB stigma as a significant obstacle to achieving the goals of the End TB Strategy. Stigma related to tuberculosis (TB) comes in several forms, each contributing to the delay or avoidance of care. Social stigma involves the fear of being rejected, isolated, or discriminated against by others—such as family members, neighbors, or employers—because of a TB diagnosis. In many communities, people with TB are unfairly seen as contagious, unclean, or responsible for their illness, which leads to social exclusion. This form of stigma is particularly damaging in close-knit communities where relationships and reputation are deeply valued.

Self-stigma occurs when individuals internalize negative public attitudes, leading to feelings of shame, guilt, or worthlessness. This can cause people with TB to hide their symptoms, deny their condition, or avoid seeking treatment altogether.

Institutional stigma, on the other hand, refers to biases and discriminatory practices within healthcare systems—such as health workers showing fear, avoiding physical contact, or providing poorer quality care. This type of stigma can reinforce feelings of inferiority and discourage future health-seeking behavior. The Stop TB Partnership has reported that stigma from health workers and structural barriers in clinics—such as lack of privacy or insensitive communication—are major obstacles to TB care. WHO (2022).

In many parts of the world, cultural misconceptions about tuberculosis (TB) continue to fuel fear, stigma, and delayed treatment. In some communities, TB is wrongly believed to be a curse, a punishment from the gods or ancestors, or a sign of spiritual impurity. People may see it as something that only affects those who have committed moral wrongs or broken cultural taboos. These beliefs are especially common in certain rural areas across Africa and Asia, where traditional and spiritual explanations of illness often coexist with modern medical knowledge. For example, a study in Ghana found that some people believed TB was caused by witchcraft or a family curse, and sought help from spiritual healers instead of health clinics.

Adeoye et al. (2024), in a study conducted in Nigeria, revealed through thematic analysis that patients’ perceptions of tuberculosis were shaped by a complex interplay of cultural, spiritual, and biomedical beliefs. Many participants questioned the germ theory of disease, attributing TB to witchcraft or spiritual attacks. The study also uncovered widespread beliefs in hereditary transmission, associations between tobacco use and TB, and confusion about the nature of the infection—all of which highlighted the influence of socio-economic disparities on health understanding.

Another widespread belief is that TB only affects the poor, unhygienic, or immoral, reinforcing stereotypes that people with the disease are somehow responsible for their condition. In some societies, TB is associated with shameful living conditions or social failure, which causes individuals to hide their symptoms and avoid being labeled.

These cultural misconceptions vary across regions. In parts of South Asia, for example, TB is seen as a hereditary disease that ruins marriage prospects, especially for women. In Nigeria and Kenya, it may be viewed as a contagious “family disease” or spiritual attack. These beliefs increase secrecy and prevent people from seeking timely medical help, which not only worsens their own health but also increases the risk of spreading TB in the community.

Stigma has a powerful and damaging effect on treatment-seeking behavior for tuberculosis (TB). When people fear being judged, isolated, or rejected by their families and communities, they are more likely to hide their symptoms or avoid clinics, even when they suspect they are ill. This delay in seeking care not only puts their own health at risk—allowing the disease to worsen—but also increases the likelihood of spreading TB to others. In many high-burden countries, patients report avoiding health facilities because of the shame attached to a TB diagnosis or fear that others will find out.

Findings from Nyasulu et al. (2018) among community members in Ntcheu District, Malawi, revealed that most participants believed tuberculosis was curable and indicated a willingness to seek diagnosis if they experienced symptoms. However, concerns about how TB spreads and the social consequences of a diagnosis—such as stigma and discrimination—created apprehension. These perceptions negatively influenced participants’ attitudes and behaviors toward seeking diagnosis and initiating treatment.

Stigma can also lead to incomplete or interrupted treatment. Individuals who feel embarrassed or discriminated against may stop taking their medication or fail to complete the full course, which is critical for curing TB and preventing drug-resistant strains. Studies have shown that people who experience stigma are less likely to return for follow-up care or adhere to treatment plans.

According to a 2022 study in BMJ Global Health, stigma is one of the leading barriers to TB treatment completion in countries like India, Nigeria, and South Africa. Tackling stigma through education, supportive counseling, and community engagement is essential for improving treatment outcomes and breaking the chain of TB transmission.

In many parts of the world, cultural misconceptions about tuberculosis (TB) continue to fuel fear, stigma, and delayed treatment. Early testing, identification and treatment of tuberculosis is highly recommended.

Data and case studies from high-burden countries clearly show how stigma discourages people from seeking TB care. For example, a 2020 study in India found that over 50% of TB patients delayed visiting a healthcare facility by more than one month after symptoms appeared, primarily due to fear of stigma and discrimination.

Nigeria remains one of the countries most affected by tuberculosis (TB) globally, as highlighted in the 2024 State of Health of the Nation report. The country is among the 30 high-burden nations for TB and continues to be a priority for addressing drug-resistant TB (DR-TB) and TB/HIV co-infections. It currently ranks 6th worldwide and 1st in Africa in terms of TB burden, accounting for roughly 4% of global TB cases. Encouragingly, in 2023, Nigeria achieved its lowest TB incidence rate within a three-year period, with every state recording a decline compared to 2022.

Despite this progress, certain states—such as Abia, Gombe, Jigawa, the FCT, Yobe, Borno, Edo, Delta, Ebonyi, and Kogi—reported incidence rates exceeding 10%, indicating a need for more focused public health responses. The report also revealed notable regional disparities, with states in the South-East and South-South recording generally higher TB incidence rates than their northern counterparts. These differences point to the importance of deeper investigation into the underlying causes, including unequal access to healthcare services, socio-economic challenges, and gaps in diagnostic coverage.

Many participants reported hiding their illness from friends and family, fearing job loss or social rejection. Some even used alternative medicine or self-treatment to avoid being seen at TB clinics. This delay led to more severe disease progression and increased transmission within households and communities.

A similar pattern was observed in Nigeria, where a 2021 study published in International Journal of Infectious Diseases revealed that 30% of patients avoided public TB clinics and instead sought treatment from private According to the Nasarawa State Ministry of Health, 35 residents lost their lives to Tuberculosis (TB) in 2024, out of the 8,190 cases recorded in the state. The deaths were attributed to the severity of their infections or informal providers due to concerns about being publicly identified as having TB.

The study noted that men, in particular, feared loss of respect and social status, while women were more likely to be blamed for bringing disease into the household. These findings demonstrate how stigma not only delays diagnosis but also affects where and how people choose to receive care—often leading to incomplete treatment and worse outcomes.

Delayed diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis (TB) have serious consequences for individuals, families, and entire communities. For the person affected, postponing care allows the disease to progress from a mild to a severe stage, often leading to permanent lung damage, disability, or death.

TB is curable, but when left untreated, it becomes much harder to manage, especially in children, people living with HIV, and those with weakened immune systems. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an untreated person with active pulmonary TB can infect up to 10–15 other people each year, making delay a key driver of community transmission.

At the public health level, delayed treatment also contributes to the emergence of drug-resistant TB. When people start treatment late or stop midway due to stigma or side effects, the TB bacteria can become resistant to standard medicines, leading to more complex, expensive, and less effective treatments. This makes TB harder to eliminate and places a greater burden on already stretched health systems.

Economically, delayed care leads to higher healthcare costs, longer hospital stays, and loss of income for patients and their families. Ultimately, breaking the cycle of stigma and encouraging early diagnosis and treatment is not only a medical necessity but also a social and economic imperative for TB-endemic countries.

Several interventions around the world have successfully helped reduce the stigma associated with tuberculosis (TB), especially through community-based education and awareness campaigns.

In countries like Uganda and India, programs that train former TB patients to share their experiences publicly have helped challenge common myths and change people’s perceptions. These efforts show that TB is treatable and nothing to be ashamed of. In Kenya, school health programs and community drama groups have been used to educate both children and adults about TB causes, symptoms, and treatment, which helps reduce fear and misinformation.

In India, the Axshya Project supported by the Global Fund has trained community volunteers to go door-to-door educating people about TB symptoms, prevention, and treatment. This personal approach has helped correct myths and build trust, leading to earlier diagnosis and reduced stigma.

Peer support groups—where TB survivors share their stories—are powerful tools for reducing shame and fear. In South Africa, for example, survivor-led groups have empowered others to speak up, access treatment, and support their peers. Religious and community leaders also play an important role by openly discussing TB in mosques, churches, and town meetings, which helps normalize the conversation. Additionally, media campaigns on radio and TV have helped counter misinformation. For instance, Nigeria’s Stop TB Partnership runs public service announcements and radio dramas to correct cultural myths and promote early treatment.

While HIV stigma is often linked to moral judgment, sexuality, or perceived promiscuity, TB stigma is more closely tied to poverty, poor hygiene, or weakness, making it harder for people in affected areas to seek care without being labeled or rejected.

Making healthcare facilities more confidential and welcoming is crucial. People are more likely to seek care if they feel they won’t be judged. WHO’s End TB Strategy emphasizes patient-centered care that respects privacy and dignity. Some countries have introduced fast-track TB testing, separate waiting areas, and trained staff on how to treat patients respectfully and without bias. These small changes build trust and help reduce stigma in hospitals and clinics. (https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/the-end-tb-strategy).

In 2024, Benue State diagnosed 10,618 tuberculosis (TB) cases and enhanced its diagnostic capacity by deploying five portable digital X-ray units and eight Truenat machines. Kano State recorded 33,690 TB cases in the previous year, achieving an 83% notification rate with 28,169 cases treated, and provided care for 1,731 children under its TB programme. The state also operates 1,391 DOTS sites and over 300 diagnostic laboratories equipped with GeneXpert and Truenat machines. Lagos State confirmed approximately 15,000 TB cases in 2024, according to a Premium Times report.

To effectively combat tuberculosis (TB) stigma and reduce its devastating impact, a multifaceted and inclusive approach is needed. Governments and health authorities must invest in community-based education programmes that demystify TB, correct myths, and emphasize that it is preventable and curable. Culturally sensitive messaging—delivered through trusted community leaders, TB survivors, religious figures, and local media—can play a key role in changing harmful beliefs and attitudes. Training health workers to provide confidential, non-judgmental care is equally critical. Healthcare facilities should be equipped to protect patient privacy and promote dignity to encourage early and continuous treatment-seeking.

Nigeria has made notable progress in tuberculosis (TB) control, recording a historic case notification level of approximately 371,000 in 2023 and surpassing 400,000 in 2024, indicating a significant improvement in TB surveillance and detection. Treatment coverage has also advanced, with an estimated 79% of identified TB cases currently receiving care. However, major service delivery gaps persist, as data from the Nigeria Bureau of Statistics (NBS) shows that only 16% of health facilities nationwide are equipped to diagnose and treat TB, with significant disparities across regions.

Policymakers must also strengthen support systems such as peer networks, mental health services, and financial assistance for TB patients, especially those at risk of discrimination and economic hardship. International organizations like the World Health Organization (WHO) should continue supporting national TB programs with funding, research, and policy guidance—such as outlined in the WHO End TB Strategy, which prioritizes stigma reduction. Countries can also learn from success stories; for instance, Egypt’s achievement of malaria-free certification shows what is possible when there is strong political will, public education, and integrated health action. Ending TB stigma is not just a health issue—it is a matter of human rights, dignity, and social justice. The time to act is now.

Comments