“I nearly died that day”: How Ignorance, Misdiagnosis and Stigma fuels Tubercolosis

The hidden scars of TB stigmatisation silences Nigeria’s affected victims.

By Precious Nwonu

Enugu, Nigeria – At 25, Sandra (not her real name) still recalls the shock she felt when she was diagnosed with tuberculosis (TB). “It was hard initially. In this country, when you’re diagnosed with tuberculosis, it’s like a death sentence, more like having HIV. It’s really disturbing,” she said, her words mirroring Nigeria’s pervasive TB stigma.

Sandra’s symptoms began like a common cough, self-treated with antibiotics. “I thought it was a normal cough… but after two days it came back. It became persistent, so I went to the health facility,” she explained. Counseling shifted her mindset. “I discovered it’s curable. Once you’re taking your medication and you’re constant with your drugs, you will recover in no time.”

But it was stigma she experienced from her friends that cut deeper than the illness. Her friends distanced themselves, fearing infection. “It became clear to me they were not really my friends. I really felt pained by their actions… this has taught me not to stigmatise people because of their TB status. I used to be like that until it happened to me.” Sandra travels monthly to Enugu State Medical Centre (20km from home), spending over ₦1,000 on transport.

Women Bear the Brunt

In communities where women are expected to keep homes “clean” and families healthy, a TB diagnosis brands them “unclean” or failures. Margret, a widow and petty trader, travels 50km monthly to Enugu State Medical Centre, hiding her status from children and neighbors. “Nobody knows about my TB status. I don’t want people to find out and start avoiding me or gossiping about me and my children,” she said. Her children assist at home due to her leg pain; she’s on TB drugs, and they take preventive meds.

Ebube, a trader, nearly died after labs misdiagnosed her symptoms as “cold.” “I wasn’t myself at all. I nearly died that day,” she recalled, her condition critical before TB treatment began at Eastern Nigeria Medical Center (ENMC). Neighbors supported her, but she keeps her status secret at work. “I don’t want them to know. It might affect my business.”

Patricia Nathaniel travels 6.7km to Ikirike Health Centre for trusted care. “I want my friend Justina (the health worker) to treat me. I trust her and I don’t mind coming this distance.” Agnes, a 59-year-old fruit seller, kept her diagnosis secret: “I don’t think anyone apart from my family members knows I have. I didn’t tell anyone, and it’s not written on the forehead.”

TB: A Major Public Health Crisis to be Prevented

Tuberculosis, an infectious disease caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis, most often affects the lungs but can attack other body parts. It spreads through the air when a person with active TB of the lungs or throat coughs, sneezes, speaks, or sings. Not everyone infected becomes sick: some carry the bacteria without symptoms, while others develop active disease when the bacteria overcome the body’s defenses.

While treatment coverage of Tuberculosis has improved in recent years in Nigeria, many people with TB are still not diagnosed or enrolled in care. Recording over 200,000 new infections each year, according to the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, TB can no longer be handled with kid gloves. Communities and health workers must join hands to fight this menace and prevent it from becoming a national health crisis.

Dr. Odo Chidebere, Enugu State’s TB, Leprosy and Buruli Ulcer Control Programme Manager, calls TB “a major public health problem” in Nigeria. Stigma blocks care as more patients avoid local clinics, traveling far to hide diagnoses.

Stigma around TB Affects Everyone, but it often Hits Women Harder.

In many communities, women are expected to keep their homes clean and families healthy. When a woman is diagnosed with TB, some people see her as “unclean” or as someone who has failed in her role. Others wrongly assume she must also have HIV. This perception makes women feel ashamed and afraid to speak up or seek help.

Because of this fear, many women delay going to the hospital when they start coughing or feeling weak. They hide their symptoms so that neighbours or relatives won’t suspect anything, or they travel long distances to access treatment where no one knows them.

Health experts say this delay worsens the illness and increases the risk of infection to others. The National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Control Programme (NTBLCP) reports that stigma remains one of the biggest reasons people refuse to get tested or complete their treatment.

Stigma also brings social and emotional pain. Some women are avoided by friends and neighbours after their diagnosis. Others are abandoned by partners or lose their jobs. Women who depend on daily income may struggle to pay for transport to health facilities or to care for their children while undergoing treatment.

“People feel that just talking with someone with TB will infect them,” Dr. Odo said. “TB isn’t transmitted by hugging, talking, kissing. We need public understanding to encourage, not isolate, patients.” Women seek care more than men, but stigma affects all. “The treatment for men and women is the same. We only consider weight,” she added. Advanced cases are more common in men who delay care. “Most men will say there’s no time . . . They visit only if drugs aren’t healing.”

“Nobody knows about my TB status”

Margret, a widow and petty trader, began experiencing serious leg pain that made it difficult to walk or carry out her daily activities. Her children had to assist her at home. At first, she thought she had been poisoned and started taking medication for poison, but the pain persisted. A neighbour, whose brother worked in a health facility, advised her to go for further testing. “I told him I didn’t have money, but he assured me not to worry, that it would be taken care of. When I got to the medical centre, a health worker asked me some questions before I did the tests. After the results came out, I was told I had TB,” Margret said.

Before the leg pain started, she had experienced a serious cough that later subsided. “When the leg pain began, I noticed the cough returned, though not as severe. I also had frequent fever alongside the leg pain,” she said. “I was given drugs to help me recover, and I was also given drugs for my two children, though they don’t know about my TB status.”

The distance from Margret’s house to the medical centre is about 50 kilometres. She travels there by public transport, but insists that the distance is worth it for quality care and privacy. “Nobody knows about my TB status, not even my children,” she said. “They only know I’m on medication. I refused to explain when they asked because I don’t want people to find out and start avoiding me or gossiping about me and my children.”

The Cost of Silence : ” I nearly died that day”

Ebube (not her real name), a trader in her early forties from Agbani, began experiencing a severe cough and body pains but had no idea it was TB. “When it started disturbing me, I didn’t know it was TB,” she said. She visited several labs in Agbani, where she was repeatedly told it was “cold”. “They prescribed some drugs for me…but I wasn’t getting better. It was really disturbing me, and every day I cried,” she recalled.

On 30 December 2024, her condition became critical. “I wasn’t myself at all. I nearly died that day,” she said. A friend called and, after hearing about her symptoms, offered to take her to a lab near Uwani, close to Eastern Nigeria Medical Center (ENMC). Her throat pain stopped after taking the prescribed medication, but “the cough continued,” prompting her to return with her friend. “When we finally met the doctor, he said I had TB and referred me to Eastern Nigeria Medical Center (ENMC). He even called the doctor there to inform them I was coming,” she said.

At ENMC, tests confirmed TB and she was placed on treatment. “I didn’t miss a single day because I knew what I had suffered. I was told I would take the drugs for six months and that I would recover.” People in her neighbourhood supported her. “They saw the pain I went through…but they didn’t avoid me. Instead, they showed love, care, and concern,” she said. But she keeps her status secret at her business location. “I don’t want them to know. It might affect my business.”

Justina Odoh, TB focal person at Ikirike Health Centre, stressed awareness: “The simple approach is enlightenment. By the time they’re told people have been coming and getting cured, that it is not a death sentence but curable, people embrace treatment.” While TB drugs have side effects such as dizziness and sun sensitivity, these usually subside after two months she explains.

Inside the Health Centres and the Role of the Ministries of Health

At Ikirike Health Centre, Justina Odoh explained: “When people come with symptoms, we screen. If TB’s suspected, we send sputum to ENMC lab. If positive, they get meds.”

She also noted a disturbing occurrence where people who are experiencing fever, and other kinds of symptoms reject treatment from free public system because of fear of recognition, only to pay for services elsewhere. “Knowing fully well everything is free here, they choose to still go out where they are likely to meet people that will extort from them, people that are not sincere like us. They tend to pay for the drug meanwhile it’s free.”

On approaches to make it easier for women to seek care, she stressed the importance of awareness. “The simple approach is enlightenment. By the time they are told that people have been coming and getting cured, we tell them when they hide their sickness, it becomes dangerous to their health. But once they are open about what is disturbing them, they get cured. There’s a need to create more awareness, like radio jingles, to tell people it’s not a death sentence; it’s curable.”

She acknowledged that TB drugs have side effects. “Some feel dizzy, some are affected under the sun, others have different reactions. These side effects often discourage patients, but they usually stop after the first two months,” she said.

“Poverty, shame and carelessness”

Another medical practitioner at ENMC, Dr. Donald Aneke, offered further insight into how stigma affects individuals diagnosed with TB. “Till today, TB is still associated with poverty, shame and carelessness in our communities, so you’d observe that patients are already labelled with those tags even before we have confirmed diagnosis,” he said. “Stigma takes several forms: social isolation, family members avoiding them, refusal to use their plates, spoons, or refusing to enter their rooms. There is also the blame game where they act like the patient must have been living dirty or brought it on themselves. There is also discrimination where schools and workplaces refuse to allow patients back even long after they are non-infectious.”

He said stigma is driven by TB’s perceived link with HIV, lack of information and class prejudice. “Some people still think it’s incurable. Some people also link it with poverty and wouldn’t want to be seen as poor.” Stigma heavily influences patients’ willingness to seek care. “Many patients delay presentation and try several treatments before coming to the hospital because of fear of being labelled,” he said.

The mental and emotional consequences can be long-lasting. “Many have had to deal with anxiety and depression, even after they’ve been cured. They battle with confidence and self-esteem issues and all these are worsened by social withdrawal,” Dr. Aneke added.

He believes education, confidentiality and patient voices are central to reducing stigma. “If people are aware that it is curable and patients are mostly not infectious after a few weeks of treatment, then the stigma would reduce,” he said. “When counselling patients, we should also counsel their family members. We should maintain patient confidentiality and be as discreet as possible. Healthcare workers should also be trained because sometimes, stigma starts with health workers. And I think we should empower cured patients as ambassadors, helping them share their powerful testimony with the world.”

To further address the distressing outcomes from stigma, Dr. Odo said the Ministry of Health supports daily screening, receives TB reports, and drives awareness in communities, churches, and markets. “The Buruli Ulcer and TB Programme shows they’re concerned about this communicable disease through such outreaches.”

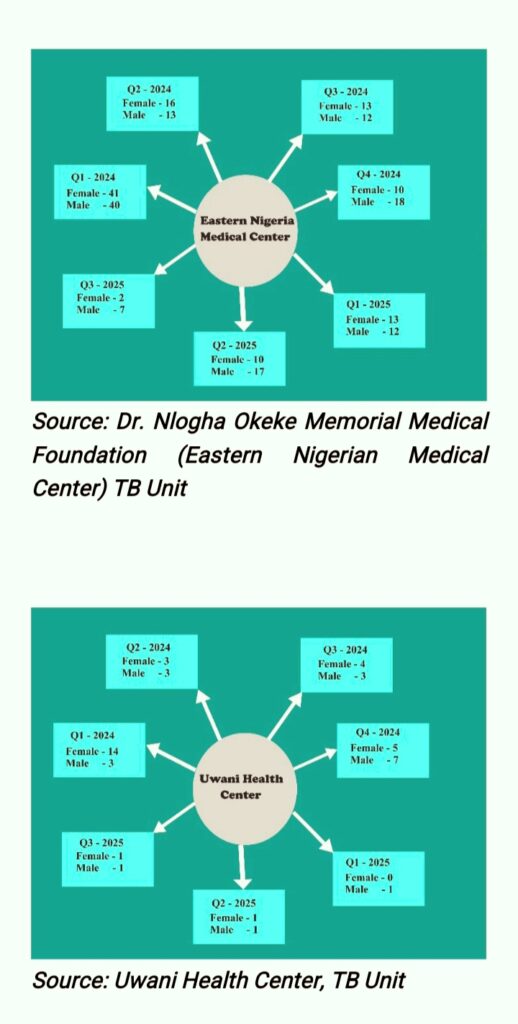

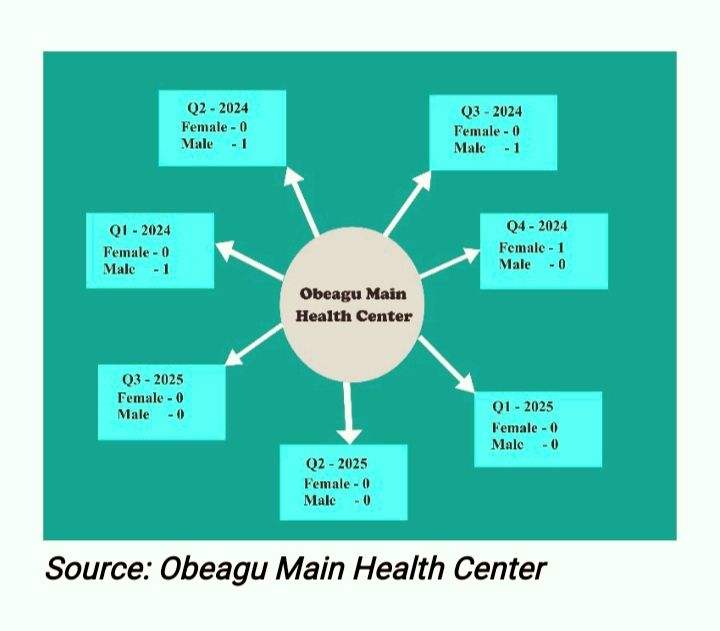

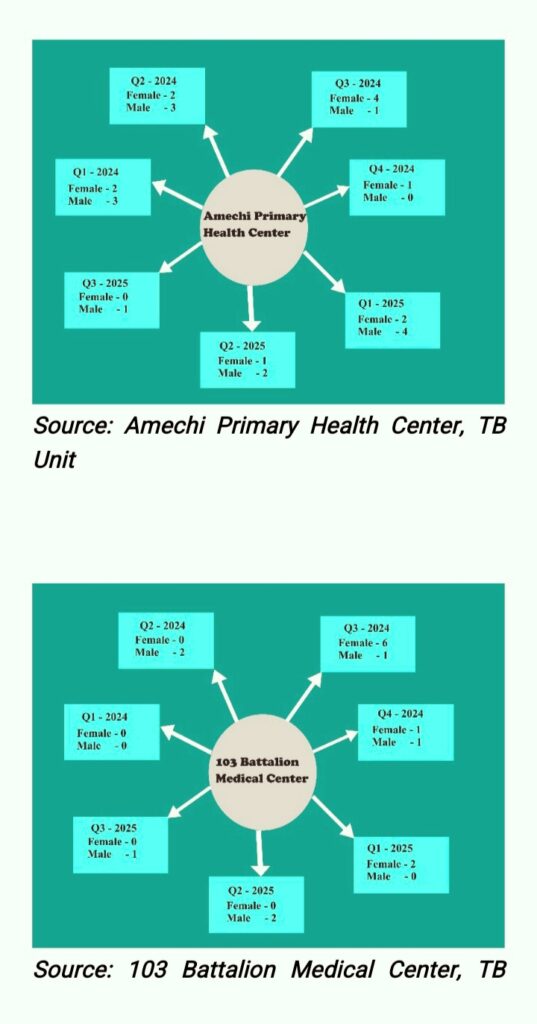

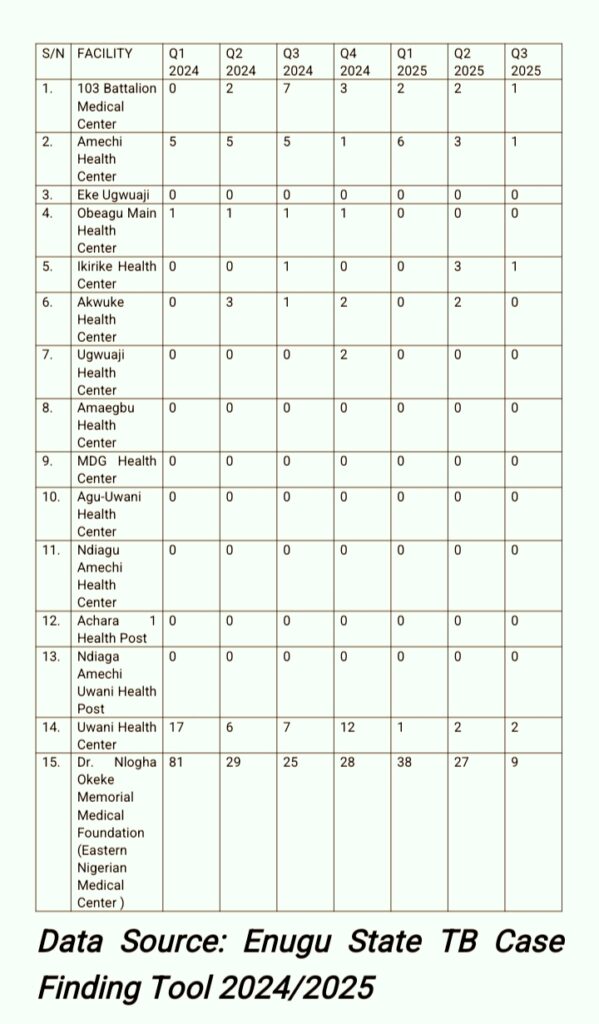

TB Data Collection: Enugu-South Local Government Area

In Enugu State, there are fourteen (14) public health facilities. I visited each facility to collect data on positive TB cases, including the number of male and female patients for each quarter from 2024 to the third quarter of 2025. The information was obtained using the Enugu State TB Case Finding Tool 2024/2025 to ensure a comprehensive and accurate dataset.

During the research, I observed that both health workers and TB patients frequently mentioned a private medical facility, Dr. Nlogha Okeke Memorial Medical Foundation (Eastern Nigerian Medical Center), which has a DOT health center equipped with a GeneXpert machine for TB testing. Health workers highlighted that they send sputum samples of suspected cases there for testing, while patients indicated a preference for receiving treatment at this facility. Consequently, I visited the medical center to collect its data as well.

Below are the compiled TB case data from each health facility.

“This content received support from the Thomson Reuters Foundation as part of its global programme aiming to strengthen free, fair and informed societies. Any financial assistance or support provided to the journalist has no editorial influence. The content of this article belongs solely to the author and is not endorsed by or associated with the Thomson Reuters Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Foundation, Thomson Reuters, Reuters, nor any other affiliates”.

Comments